By: Ian Longley

So farewell RMA and 20 years of doing air quality management the way we do it

In December 2025, the NZ government revealed its replacement for the Resource Management Act (RMA) which has governed how we manage ambient air quality for over two decades.

We now have a Planning Bill and a Natural Environment Bill and, like many others, I’m trying to get my head around what it means for air quality.

In the meantime, it did make me reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of the regime that we’ve grown used to, but was still relatively fresh when I (and my Air Quality Collective colleagues) arrived in New Zealand nearly 20 years ago.

Back then, the new deal was the National Environmental Standards, which came into force as part of the Resource Management Regulations in 2004. These were largely a pick-and-mix selection from the WHO Guidelines, and were very similar to the UK’s Air Quality Objectives that I had grown used to in the previous decade.

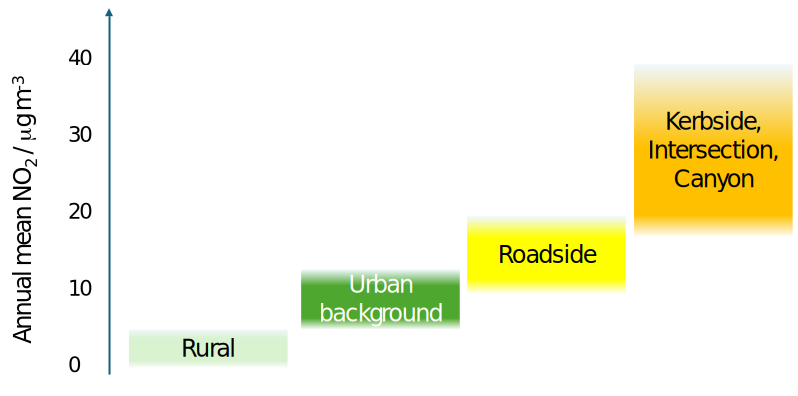

But I quickly learned that it was only the PM10 standard that really mattered, due to widespread breaches across our towns and cities from the largest cities to some of our smallest towns. And although there was some scepticism from many quarters, it was obvious to me who the culprit was. One look at the hourly PM10 data from, say, Alexandra, with its rapid deterioration around 4 pm on still winter evenings, and the absence of high PM10 when it was warm, pointed the finger directly at smoke from wood burning from home heating. We’ve since spent substantial sums on emission inventories and source apportionment studies that have just confirmed this.

The original Regulations were ambitious, with Regional Councils required to meet the PM10 standard everywhere by 2013, and significant penalties for airsheds that didn’t.

You read that right, 2013!

And here we are in 2025, with at least 9 airsheds recording PM10 exceedences this year according to LAWA, with data from Otago – which typically has one of the worst records – not yet available.

Some may recall that the Regulations were amended in 2011 when it became clear the 2013 deadline was not going to be met. The amendments pushed the data for one allowed exceedance to 2016 and full compliance to 2020.

Still, we clearly didn’t meet those goals. Why?

There is clearly one line of argument about the efficiency (or otherwise) of political, governance and management processes, and another about the ability of Councils to fund the actions that lead to air quality improvement.

There is also our reliance on the “silver bullet” solution of low-emission woodburners, which Councils have tried to incentivize as a “clean heat” option.

If you want to know whether or not this has worked, I refer you back to the PM10 data.

“Low emission” is a relative term. A town full of low emission burners will still, it seems, experience exceedences of the PM10 standard. Real-world testing has shown that a model that can comply with “low emission” testing in the lab, can often have much higher emissions in the home. Then we have the issue of urban growth which in some areas has been substantial. The number of woodburners (even if they are low emission) has grown substantially in districts like Selwyn, Waimakariri, Central Otago and Queenstown-Lakes.

Not that the previous Regulations have been ineffective. PM10 levels have – generally – fallen nearly everywhere in NZ the last 20 years, with the large-scale inequity (difference between most and least polluted airsheds) shrinking, although intra-airshed inequity remains.

But the time when the legislation is being re-written is the time to ask whether we could have done better. No matter what arrangements are put in place next, decisions made over the next year or two will determine what incentives can be put in place to progress towards clean air for all.