What if we thought about pandemics the way we think about tsunamis?

My eye was caught today by an article on how effective the pan-Pacific tsunami warning system had been following this week’s 8.8 magnitude earthquake off the cost of Russia. An estimated 3 million people around the Pacific Rim and islands were successfully told to evacuate their homes. It was noted that the Indian Ocean tsunami warning system was not set up until after the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami. Before 2004 it was considered too expensive and not a high enough priority. 2004 was certainly a learning experience but also one that led to a long-term development of precautions and procedures to implement when needed, leading to a highly effective response to this week’s event.

It made me wonder how this compares to our pandemic preparedness.

Practices and priorities around tsunamis changed in 2004. The science could offer no reason why a similar event would not happen again. The gamble involved in not building preparedness was too great and the technical investment, plus the wide-ranging public education began.

Where is the scientific evidence that a pandemic like COVID-19 cannot happen again? Yet where is the investment? Where is the public education? How big is the risk we seem to be taking in paying so little attention to building preparedness, or even learning from our experience?

But what do I mean by preparedness? I can tell you what I don’t mean. Relying on pharmaceutical technology to save us is a very limited solution because of the time lags between the outbreak and the successful development and delivery of the vaccine, especially to those at the back of the queue (often the most vulnerable anyway).

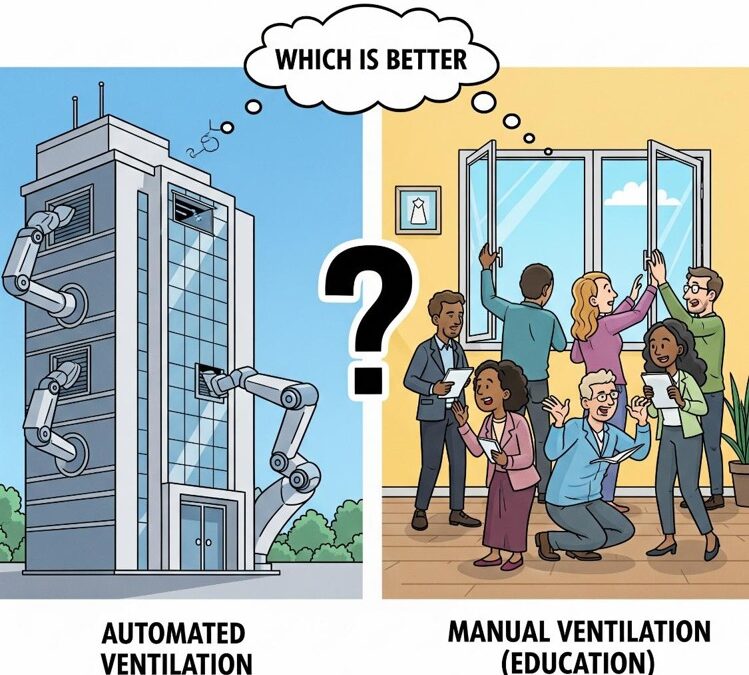

No, to me being prepared means having measures in place BEFORE the emergency arises. And ideally measures that benefit all people equally and simultaneously.

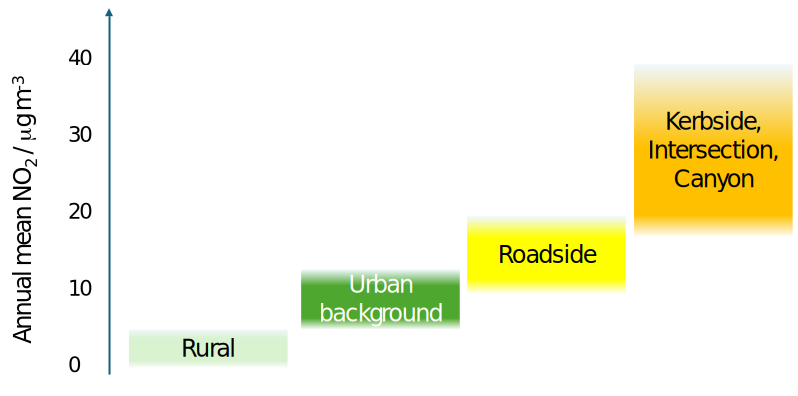

In March 2020 we locked down. We did this because we had no way of knowing which spaces posed a major risk of infection and which – through good ventilation or air filtration – posed a minimal or manageable risk. 18 months later Auckland was still partly locked down. We had made almost no progress in assessing the risk posed by shared air. Now in 2025 I would argue we still don’t really have much idea which spaces could feasibly be kept open during a similar pandemic, and most people would not know how to manage the air in their spaces when (not if) a similar outbreak occurs.

It is, of course, 21 years since the Boxing Day tsunami – 21 years for risks to be assessed, investments to be made, education to be rolled out and iteratively improved. Maybe we can do the same for indoor airborne infection risk. But hopefully before the next outbreak.