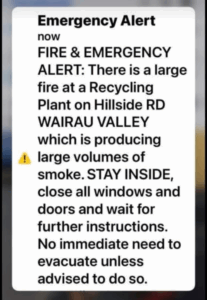

Last Thursday (24th April) the mobile phones of thousands of Aucklanders simultaneously throbbed and wailed as a civil defence emergency announcement was broadcast across the city. A huge and devastating fire had broken out at a recycling centre on the North Shore sending huge clouds of thick black smoke into the air. The emergency announcement directed residents to “stay indoors and shut doors and windows”. My wondering for today is how many actually did?

Last Thursday (24th April) the mobile phones of thousands of Aucklanders simultaneously throbbed and wailed as a civil defence emergency announcement was broadcast across the city. A huge and devastating fire had broken out at a recycling centre on the North Shore sending huge clouds of thick black smoke into the air. The emergency announcement directed residents to “stay indoors and shut doors and windows”. My wondering for today is how many actually did?

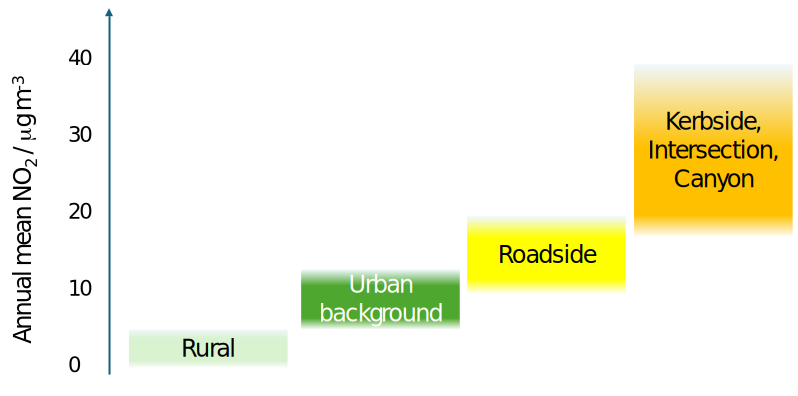

I can tell you for sure who didn’t. Me. I live only a few kilometres form the site of the fire and I was at home when the sirens blared. I had no plans to go anywhere, so I was fine with the “stay indoors” bit. My lack of action on the doors and windows, however, had nothing to do with insolence or laziness. Rather, it was the result of my professional awareness and general geekiness which led me to know that there was a strong easterly wind placing my home upwind of the fire with pretty much zero chance of the plume travelling against the wind towards me.

Had I been downwind, however, it would have been a different matter. I have spent a few years running experiments in homes and directly observing just how effective closing doors and windows can be in reducing (not eliminating!) infiltration of smoke into the home. And reducing dose can make the critical difference between coping and poisoning.

Had I been downwind, however, it would have been a different matter. I have spent a few years running experiments in homes and directly observing just how effective closing doors and windows can be in reducing (not eliminating!) infiltration of smoke into the home. And reducing dose can make the critical difference between coping and poisoning.

But I also know from experience that some people don’t see it that way. It’s the classic human cognition problem of black-and-white thinking. We all seem to have a sub-conscious default approach to risk of “safe or deadly”. Being indoors with doors and windows shut either offers me full protection or no protection at all.

Sometimes we need other triggers, other signs to tell our brain that the threat is real or not. Basically – can you see or smell the smoke? The nature of urban environments is that most people won’t see the smoke unless they are very close. More likely they will smell it before they see it. And then a second mental heuristic can often kick in – it’s too late to do anything, so I might as well just ride it through. But is it too late?

That’s actually a rather subtle question. Closing doors and windows after smoke has entered the home will indeed slow the rate of ingress and hence contribute to reducing dose. But, if the smoke has passed, then closing doors and windows traps the infiltrated smoke and actually prolongs exposure and increases dose. The tricky balancing act is to minimise ventilation if the smoke is outside, but maximise ventilation once the smoke has passed.

In most realistic situations of urban fires, it is very hard to know when the smoke has passed, and when to ventilate. We therefore invoke the precautionary principle and assume the smoke is still present outdoors until we are sure it has gone and is not coming back. That will increase dose over the theoretical minimum, and hopefully that will be an acceptable outcome for most.

But what of our more sensitive members of the community? Those for whom any increase in dose could lead to discomfort, illness or even immediate risk to life? For them, I believe that air filtration is the best available solution. Filtration is available in the form of appliances you can buy at the whiteware store, or can be built into HVAC systems. But it has to be planned for if you want it available in an emergency situation.

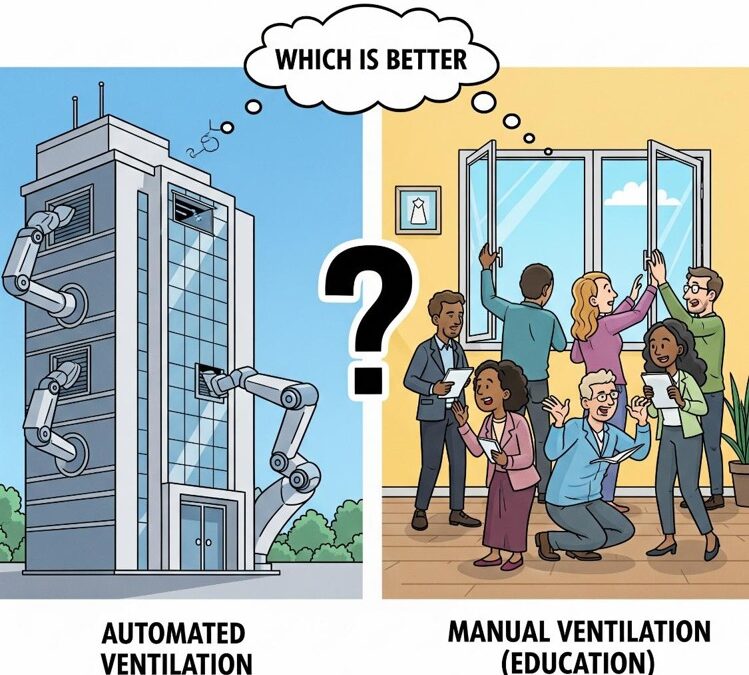

Another approach is to use outdoor air monitoring to determine when (and where) the air is smoky and when it has passed. This requires a quite different format of monitoring than the relatively sparse network of stations run by the Council. It means installing monitors outside critical locations where sensitive individuals may reside and feeding that back to some form of control system. Ideally it means pooling all of that data, combining it with other crowd-sourced data from tens, hundreds or even thousands of privately-owned monitors, to create live air quality maps than can then be used to directly inform human or automated decisions. But again, that doesn’t happen unless it is planned for.

Civil defence emergency announcements are experiencing some adoption problems. Warnings are necessarily broad in their scope, especially for risks like fire smoke where the exact locations at risk are hard to predict. The result is that many (maybe most) of the people who receive the warning – including me in the case of last week’s fire – end up not actually exposed to the hazard, because the wind took it elsewhere. For many, this undermines the messaging raising the risk it will be ignored next time.

I speculate, however, in lieu of my imagined sense-and-control network that doesn’t yet exist, that our best understanding of where the smoke was and who it was affecting could be gathered through comments, photos and videos on social media. These “observations” contain physical data, but also emotional data that can be extracted and interpreted by computing techniques like sentiment analysis. And emotional data can be more powerful in triggering actions than physical data. It is when the community “sees” and “smells” the smoke through their social media networks – effectively extending our senses to make the smoke seem “real” – that physical data and formal messaging hits home.

In short, lots of technologies just waiting to be harnessed to make sure warnings are delivered to where they are needed without compromising their credibility, so that recipients are willing and able to act on them.